Nonlinear elasticity theory plays a fundamental role in modelling the mechanical response of many polymeric and biological materials. Such materials are capable of undergoing finite deformation, and their material response is often characterised by complex, nonlinear constitutive relationships. Because of these difficulties, predicting the response of such materials to arbitrary loads requires numerical computation (usually based on the finite element method).

The steps involved in the construction of the required finite element algorithms are classical and straightforward in principle, but their application to non-trivial material models are typically tedious and error-prone. We believe our automated computational framework for nonlinear elasticity, CBC.Twist, is an elegant solution to this problem.

Hyperelastic dolphin in a flow!

CBC.Twist aims to allow researchers to easily pose their problems in a straightforward manner, so that they may focus on higher-level modelling questions, without being hindered by specific implementation issues. It is built atop the FEniCS project, and is collaboratively developed free software. We’d love for you to try it and tell us what you think!

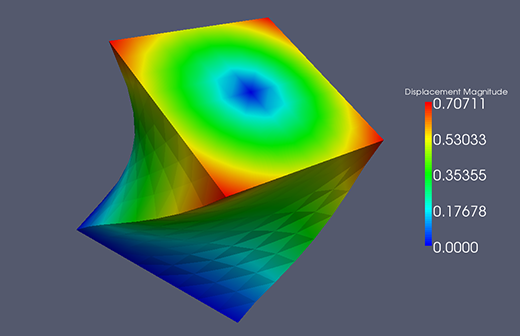

The capabilities (and elegance!) of CBC.Twist is best captured in the following example, a hyperelastic block being twisted by 60 degrees.

# Import utility classes from cbc.twist

from cbc.twist import *

# Define the quasi-static hyperelasticity problem

class Twist(StaticHyperelasticity):

def mesh(self):

return UnitCube(8, 8, 8)

def dirichlet_values(self):

clamp = Expression(("0.0", "0.0", "0.0"))

twist = Expression(("0.0",

"y0+(x[1]-y0)*cos(t)-(x[2]-z0)*sin(t)-x[1]",

"z0+(x[1]-y0)*sin(t)+(x[2]-z0)*cos(t)-x[2]"),

y0=0.5, z0=0.5, t=pi/3)

return [clamp, twist]

def dirichlet_boundaries(self):

left = "x[0] == 0.0"

right = "x[0] == 1.0"

return [left, right]

def body_force(self):

B = Expression(("0.0", "0.0", "0.0"))

return B

def material_model(self):

mu = 3.8461

lmbda = 5.7692

material = StVenantKirchhoff([mu, lmbda])

return material

def __str__(self):

return "A hyperelastic cube twisted by 60 degrees"

# Setup the problem

twist = Twist()

print twist

# Solve the problem and plot the solution

u = twist.solve()

plot(u)

Notice that the code above only contains information directly pertinent to specification of the mechanics problem. This includes the definition of the computational domain, material model, boundary conditions and body forces. The underlying framework parses this human-readable Python code, automatically performs several steps (including the most tedious one of them all: linearisation of the nonlinear problem) and generates efficient C++ code for finite element computation.

When run, we see quadratic convergence of the Newton-Raphson scheme used to solve the nonlinear problem and a pretty solution!

Twisting a hyperelastic block.

But the fun does not stop there. CBC.Twist includes a lot of other nifty features, including:

- Built in support for a large class of material models.

- Easy specification of additional material models using a syntax that closely mirrors how continuum mechanics is posed on paper, e.g.:

class MooneyRivlin(MaterialModel): """Defines the strain energy function for a (two term) Mooney-Rivlin material""" def model_info(self): self.num_parameters = 2 self.kinematic_measure = "CauchyGreenInvariants" def strain_energy(self, parameters): I1 = self.I1 I2 = self.I2 [C1, C2] = parameters return C1*(I1 - 3) + C2*(I2 - 3) - Support for material heterogeneity (spatially-varying material constants).

- Support for time-dependent problems incorporating energy-momentum conserving time-stepping schemes.

Additionally, the following extensions are being worked on:

- Support for multiple materials and anisotropy.

- Goal-oriented adaptivity.

- Introducing coupling with other physics (including fluid-solid interaction).

This software is part of research carried out in collaboration with Anders Logg and Kristoffer Selim at Simula Research Laboratory in 2009 and 2010. It is part of a larger project which aims to offer the same level of functionality (and ease of use) for general fluid, solid and fluid-solid interaction problems. It is available under the GNU GPL from its project page on launchpad.net.